Resource Extracting Tool for Sanitarium

reverse-engineering, game-dev ·

I played Sanitarium last year after years of it being in my backlog of games I want to play. And I gotta say, I loved it.

If you like the type of horror that doesn’t scare with jumpscares, but rather makes you uncomfortable, play it, right now.

I wanted the challenge of using the least amount of external resources I could to extract the resources in the game’s files. I’m nothing close to a professional in this and just writing for fun, so if you have experience doing these types of things, feel free to throw me some tips or corrections!

Examining the File Structure

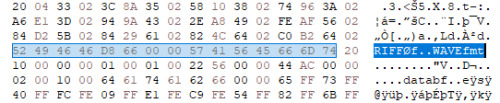

The Data folder for Sanitarium has the game resources separated into different RES.xxx files. The first three files (RES.001, RES.002, and RES.003) form a split archive. Opening RES.001 with 7zip will automatically combine them and extract the full contents. Most of these files contain WAV audio files (identified by the header RIFFxxxxWAVE), and a large chunk of RES.000 contains all the dialogue text and item descriptions from the game.

Another frequent header is D3GR, which I could not find listed anywhere as a common or known file type. My best guess is that this stands for “DreamForge (3)? Graphic Resource,” referencing the game’s developer.

Decoding the D3GR Format

Comparing different examples of this file type, there’s a common pattern in the first 4 bytes after the D3GR header, most commonly being 0x02 0x10, 0x02 0x80, or 0x02 0x00. The PCX format is from around that era and uses the first two bytes for version information, so that could be a similar approach here. The other two bytes being either 0x00, 0x10, or 0x80 means that when converted to binary, only one bit is set to 1, so this could be a bit flag for various settings.

0x02 in binary: 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 (2 in decimal)

0x10 in binary: 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 (16 in decimal)

0x80 in binary: 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 (128 in decimal)

The byte at position 0x18 consistently has values from 1 to numbers under 100. Values of 1 are pretty frequent, so I suspect this is the frame count (the number of animation frames stored in the file). If this is the frame count, there should be a matching number of offset pointers telling us where each frame starts in the file.

For this specific file, the byte at 0x18 is 0x0F (15 in decimal).

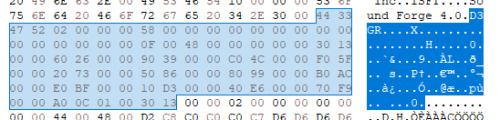

Starting from position 0x1C, we have these hex values: 30 13, 60 26, 90 39, C0 4C, F0 5F, 20 73, 50 86, 80 99, B0 AC, E0 BF, 10 D3, 40 E6, 70 F9, A0 0C, 30 13. These values are high enough to potentially be offsets (pointers to locations in the file), and we have exactly 15 of them, matching our suspected frame count. We’re still missing the offset where the actual image data starts. Many file formats include this information near the header. We have a variable number of frames, so clearly the starting position of the data section will vary as well. I verified that moving to position 0x08 plus 0x58 leaves me at what appears to be the start of the file’s image data.

So far, the likely header structure is:

OFFSET FRAME COUNT

D 3 G R | 02 ? ? ? | OF OF OF OF | ? ? ? ? | ? ? ? ? | ? ? ? ? | FC ? ? ? |

? ? ? ? | Frame 1 Offset | Frame 2 Offset...

OF = Offset FC = Frame Count

The 02 byte could indicate the type of compression. From the BMP file format specification: 0 = BI_RGB (no compression), 1 = BI_RLE8 (8-bit RLE encoding), 2 = BI_RLE4 (4-bit RLE encoding). I’m not entirely certain about this interpretation.

Finding Width and Height

With offsets, frame count, and (possibly) flags identified, we’re still missing other fundamental information that most image file formats require:

- Width?

- Height?

Most other bytes in the header are set to 0, except for position 0x1A which is 0x48 = 72 in decimal.

Looking at the start of the actual image data, there are 4 bytes with values 0x44 0x00 0x48 0x00 at positions 0xC and 0xE. In decimal, these are 68 and 72. This pattern repeats across other files, with values typically ranging from 60-170. These dimensions look appropriate for sprite graphics from a game of this era, so I believe these are the width and height values for each frame.

We now have width, height, offsets, and frame count. At this point we have enough information to at least attempt a first extraction and verify whether some of these assumptions are correct. Before writing any code, I manually navigated to the start of the data section using my hex editor and jumped to one of the calculated offsets. Sure enough, I found what appeared to be the beginning of a new frame—the pattern of 0x44 and 0x48 (width and height) repeated at the expected location.

Building the Extraction Tool

I built this tool with C++ as a console application. Since I didn’t have the color palette yet, I asked Claude to generate a temporary one for testing purposes. The objective at this stage was just to get something extracted, even if the colors were wrong.

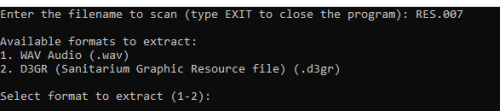

The console application is straightforward—it lets you extract both WAV audio files (much more straightforward since all the information about WAV file structure is available online) and the D3GR graphics format I’d been analyzing.

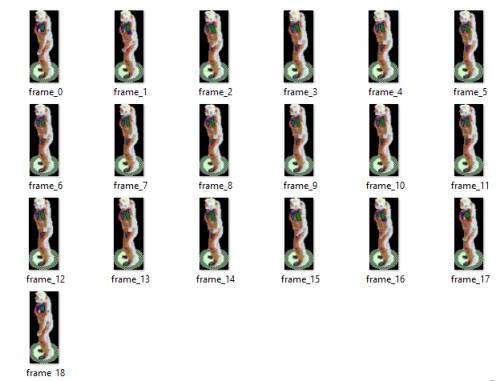

The good news is that it works. The bad news is that it looks like garbage. Since these are 256-color indexed images (common for games from this era), I need to find the actual color palette that the game uses. Without the correct palette, each pixel’s color index gets mapped to the wrong color. But even with the wrong colors, you can tell that this is the idle animation for the protagonist.

Finding the Color Palette

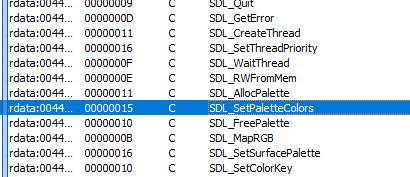

I checked the headers of all the RES files but had no luck finding embedded palette data. I figured the next logical step would be to open the game’s executable with IDA (a disassembler) and see if I could find any functions that set the palette.

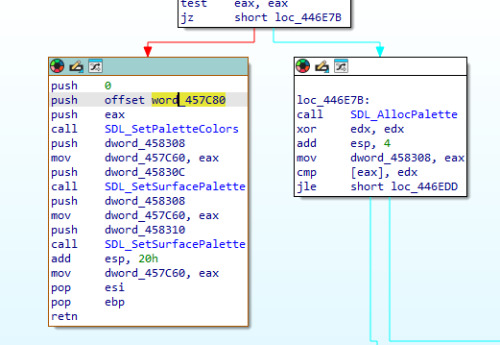

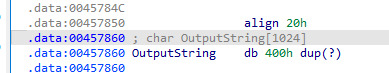

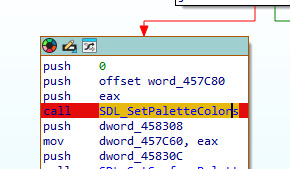

I found the SDL_SetPaletteColors function being called in this section of the code. The disassembly shows the program pushing the contents from memory offset 456C80 onto the stack to pass them to the palette function.

Even better, when examining this memory location in IDA, I can see a char array variable called OutputString with 1024 items. That’s 256 colors × 4 bytes per color (RGBA format) = 1024 bytes total; definitely the palette I’m looking for.

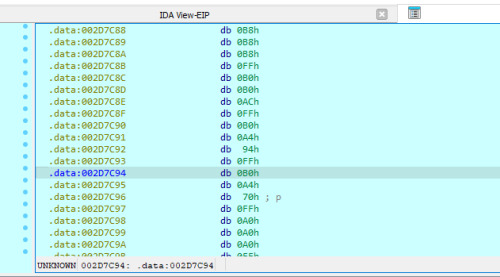

My next step was to set a breakpoint at SDL_SetSurfacePalette in a debugger and launch the game. When the breakpoint hit, I dumped the palette data from memory.

Found it! Though there could be multiple palettes in use, as it was common for games of this era to swap palettes for different scenes or effects (which is why this function exists in the first place).

The extracted images look much better now, but some colors still don’t match the game exactly (the barn appears green instead of its correct color), indicating the game likely uses different palettes for different areas.

You can find the repository for the unfinished tool here: https://github.com/zLomb/SanitUnpack

I’ve since then abandoned this project, but I’m keeping this public in case anyone finds it useful.